Tornadoes of the type that recently ripped through the Ottawa-Gatineau region aren’t the norm.

But if you ask Canadians what storm they most fear, odds are the mere threat of such phenomena frightens them more than anything else Mother Nature can throw at them.

“Tornadoes, as one might imagine, loom large in people’s minds because of movies and because of stories like Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz,” says Dr. Margo Watt, professor of psychology at St FX University in Antigonish.

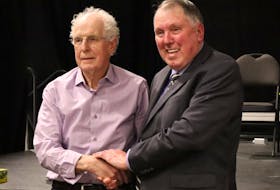

Watt has spent the better part of a decade studying the fears associated with severe weather and is considered a leader in research on the subject. With the 15th anniversary of Hurricane Juan approaching on Sept. 29, Watt took some time to share how storms affect people mentally.

One thing is clear – and her research shows it – people process storms differently. Some cower under their beds when a storm hits; others stand on the edge of the ocean to watch the waves crash in. Somewhere in the middle are people who have a healthy fear of storms, who learn from the experience.

“The average individual who gets through this event learns how to prepare better. We tend to integrate it into being better prepared. Then, we’re hopefully reducing our risk for a traumatic incident.”

Examples might be people who bought generators in case of a power outage after Juan, or people in Quebec who put in alternative heat sources after ice storms that left people without heat for days.

But there are exceptions.

Storm chasers

Watt said professional storm chasers seem to have become popular after the Second World War when former pilots began going out to gather data in the midst of extreme weather.

Today there are many recreational storm chasers. There are places in the U.S. that even offer the opportunity to take part in a storm chase as a form of tourism.

While those who aren’t as inclined to be at the centre of a storm struggle to understand the willful pursuit, Watt said storm chasers aren’t people who want to put their lives at risk.

“They’re not so much sensation seekers as they are experience chasers,” she said. “They don't like to be bored. They like to add to their experiences.”

She believes more research is needed to fully understand it, but what exists shows these people aren’t trying to be reckless.

“They’re just trying to add to their repertoire.”

RELATED:

- Storm warnings: Thanks to slowing Gulf Stream, weather is getting rougher

- PHOTOS: Hurricane Juan hits the Maritimes

- Fifteen years ago, hurricane Juan gave P.E.I. residents a wake-up call on improving emergency preparedness

- Hurricane Juan's path displaced outhouse, rabbit and trampoline for P.E.I. residents

The fear factor

There is, however, a certain subset of the population that are at great risk of experiencing mental health symptoms in the aftermath of a storm. These are people who already experience high anxiety or have a tendency to, Watt said. They are more likely to suffer post-traumatic stress after living through a major storm, or any form of traumatic incident for that matter.

“They’re also at greater risk for anticipatory fear when storms are being announced.”

Her research indicates about two to three per cent of the population are at risk for severe weather phobia, while about 10 per cent show moderate to high fear.

What’s interesting is that many of these people are fearful, even though they’ve never been impacted by a severe storm – such as is the case with tornadoes.

“The fear isn’t what they’ve been exposed to,” Watt said, adding it’s what they’re hearing about.

She said people tend to buy into pre-storm coverage.

“We elevate the alarm,” she said, even in situations where there isn’t likely to be a long-term effect.

“As someone who has worked in the anxiety field for a long time and this is my area of expertise and research, I’m always sort of mindful of the extreme language and the hyperbole.”

She said in Florida right now, there’s research being conducted on how messaging can be done better to prepare people for storms without raising unnecessary fears.

“There’s lots of work to be done in this area.”

Surviving a storm

Those that do live through a major storm can suffer acute stress or post-traumatic stress as a result. These people can become hypervigilant about weather or become extremely fearful and as a result avoid storms at all cost.

“They’re going to engage in avoidance behaviours,” she said. “They’ll cancel all appointments. They may hide underneath their bed.”

As a psychologist, though, she advises against avoidance or distraction techniques. While those may help in the short term, for people with an unhealthy fear she said the best approach is a gradual introduction into storms.

For instance, she would recommend that if someone has an unhealthy fear, they start reintroduction by talking about storms, and then maybe progress to looking at pictures or videos and so on.

Education is key, she said. The more people know about storms, the less afraid they tend to be.

She said cognitive behavioral therapy can help educate people about their own fear and allows people to identify the thoughts that keep them fearful. While these individuals tend to think about the worst-case scenario, the therapy can help them recalibrate their risk assessments, she added.

Children and storms

Parents, in particular, can play a crucial role in helping their children develop a proper mindset towards severe weather.

“My research clearly indicates the potency of parents when it comes to all types of fears,” Watt said. “We want to be careful not to model fear.”

When kids are around, people should be careful to not talk in catastrophic terms about the storms. Parents should explain about the weather event and what preparations are made.

“Help them put it in perspective in an age-appropriate way.”

Storybooks, for instance, can be a great way to talk about the subject. The key is to help them integrate it into their experience so they feel an element of control.

Ongoing research

As Dr. Margo Watt continues her research regarding psychology and severe weather she is currently working on a new survey called: Personality & Fear of Severe Weather. The project will examine people’s exposure to, and experience with, severe weather events, including the salience of weather in their daily lives, and the role of personality traits as potential risk and/or resiliency factors. To find out more or to take part, visit https://stfx.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_9F69DOwNJ2XyEoB.